What is an invasive species? There’s a section of Lynch Park in my hometown of Beverly, MA, where the land jags out into the blue plane of the ocean. The city’s Parks and Recreation offices sit on the point in a low, mossy-roofed building as humble as a gamekeeper’s cottage. Beside that, a little chlorine-smelling splash pad and a jungle gym shaped like a pirate ship. Most parents of young kids in town know it’s one of the only tolerable places to go on hot August or September days, when the air around here is the temperature and consistency of fresh bechamel: the east wind almost always blows across the headland, rolling over it cooled and refreshed by the Atlantic. On any summer weekend afternoon, it’s delicious to sit on one of the benches in this park, while the smell of charcoal and fat hangs in the haze and little one-masted sloops drift by on the tide, so close their sails look like they could knock the bowls of potato salad off the picnic tables.

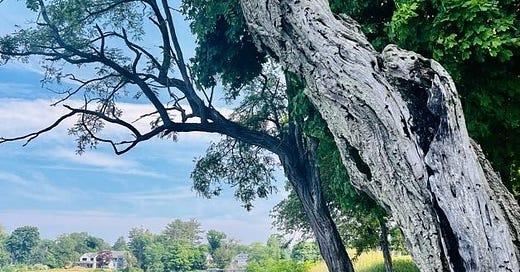

The whole outer rim of this peninsula—Woodberry’s Point, as it was called during the Revolutionary War—is ringed by Black Locusts, Robinia pseudoacacia, which stand at even intervals on the shore like the old Cost Guard patrolmen who used to walk by night with their lanterns along the outer Cape. Locusts love the sea, preferring poor soil, oblivious to the punishing coastal wind, and throwing sheets of pollen into the unquiet salt air during the middle weeks of June. These trees are sometimes considered unsung heroes of North American forests, and at other times hated for their propensity to dominate and shade open areas, a habitat that is decreasing on this continent. Yet their hanging, faceted, milk-colored flowers are as lovely as wisteria, and their lumber is as water-resistant as cedar or chestnut. I sometimes wonder why we don’t grow it more.

Almost every one of the locusts on the southern edge of Lynch Park is clasped by the long vine of a Climbing Hydrangea, probably Hydrangea petiolaris, ascending like a huge many-legged centipede up the shady northern part of its trunk. Some of these hydrangeas have reached upwards of fifty feet, a height that can take as many years to reach, since their growth rate is around twelve inches per year. It’s something to come to the park around midsummer, when the flat white pans of the hydrangea blossoms mingle with the locust flowers, a tonal froth offset by the year’s deepest greens.

But, this year, I came back to reclaim my typical bench and found that two-thirds of the hydrangea vines had been severed about a foot above the ground. What could have been the reason? There’s a longstanding debate in the U.S. about English Ivy’s relationship with trees. It’s a fine old tradition across the Atlantic to clad big oaks in ivy, but here it is said that the stems can harbor dangerous bacteria and, more pertinently, that as a groundcover it grows so fast as to shade out and kill any native competitors.

Climbing Hydrangea does none of these things, takes little from its host, and leaves nothing but a bit of root residue behind when it’s stripped from the bark. And stripped it was, from all but a few of Lynch Park’s locusts. It was strange to reflect on the logic that went into this decision. Though Climbing Hydrangea is native to Asia, it’s far less aggressive than the locusts that were probably trying to be saved. I suppose an invasive species is any plant that’s perceived as a threat to a plant you like. I moved my fingers over the crisscrossed residue of the vanished vines, a pattern like birds’ feet left in sand. By next year, that memory will be entirely gone.

Like what you’re reading here? Help grow our family of gardeners, educators, and enthusiasts by referring a friend and you can earn rewards, including PDF guides to program development, access to my top gardening tips, and more: